Toward Community in a Polarized World

What are the stories we tell ourselves about community today?

According to the Pew Research Center, many of those stories are grounded in a declining public trust in both the federal government and in our fellow citizens. Three-quarters of Americans say that their fellow citizens’ trust in the federal government has been shrinking, and 64 percent believe that peoples’ trust in each other is shrinking. Trust in nonprofits has also decreased. For those who think interpersonal trust has declined in the past generation, numerous reasons and rationales are brought to bear that make this assumption correct.

Eroding trust in our public and interpersonal lives fundamentally corrodes at the hearts of our fellow citizens--and corrodes what used to be our communities. For many, this is a deeply personal spiritual story and outcome.

Declining trust in government and increasing polarization in society result in an unenviable outcome of citizens feeling isolated and divided. A Kaiser Family Foundation study notes that 1 in 5 Americans always or often feel lonely or socially isolated, including many whose health, relationships and work suffers as a result. According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report, the rate of Americans ages 10-24 who died by suicide rose by 56 percent from 2007 to 2017. Depression rates among teens shot up 63 percent in the same time period.

Our media environments and ecosystems make it easy to adopt and opt-in to various community symbologies that give us and our communities shorthand for identities. For instance, Red vs. Blue America, which sprouted out of the 2000 Bush v Gore election fiasco and has led to folks fundamentally conceptualizing decisions like where they live based on whether it aligns with these political labels. This example is one in a larger phenomenon that the journalist Bill Bishop has coined as The Big Sort – the process of the self-segregation of Americans into like-minded communities. Bishop suggests that Americans choose to live in neighborhoods where most residents share beliefs similar to their own. The media social and political echo chambers that exist online are also geographically spatialized where people can avoid interacting with anyone who disagrees with them on political issues.

Greg Martin and Steven Webster, in an article in The Atlantic, agree that there is rapid growth of geographic polarization in the United States, but disagree with Bishop on the cause. They describe a political polarization manifesting itself geographically largely because partisan preferences are strongly correlated with population density. Further, they speak to how partisan identities now align with social identities, such as race, religion, geography (i.e. rural vs. urban) and education level, far more closely than they did a generation ago before the political re-alignments associated with the 1960s.

Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic is unearthing additional stories.

Derek Thompson writes in The Atlantic,

“Normal times do not offer a convenient news peg for slow-rolling catastrophes. When we look at the world around us—at outdated or crumbling infrastructure, at inadequate health care, at racism and poverty—it is all too easy to cultivate an attitude of small-minded resignation: This is just the way it has always been. Calamity can stir us from the trance of complacency and force us to ask first-principle questions about the world: What is a community for? How is it put together? What are its basic needs? How should we provide them?”

These are the questions we should be asking about our own world as we confront the coronavirus pandemic and think about what should come after.

These are the questions we should be asking about our own world as we confront the coronavirus pandemic and think about what should come after. The most important changes following past catastrophes went beyond the catastrophe itself. They accounted fully for the problems that had been revealed and conceived of solutions broadly. New York did not react to the blizzard of 1888 by stockpiling snow shovels. It created an entire infrastructure of subterranean power and transit that made the city cleaner, more equitable, and more efficient.

And of course, there are stories told to us. Silicon Valley is good at creating this kind of narrative, as author and co-founder of the Sacred Design Lab, Casper ter Kuile, notes:

“Venture capitalists are investing in companies that put community at the heart of their strategy.” As one VC wrote recently, “The 2020’s will belong to the entrepreneurs who can help build authentic communities.”

This is exciting stuff! Just imagine, a whole new generation of products and services that intentionally foster human connectivity! But can they live up to their promise? And isn’t it also a little scary?

Just as social networks, especially Facebook, used the language of friendship to describe the simple act of allowing our attention to be captured by someone's status update, we're already seeing the denigration of the word 'community.'

My team at Sacred Design Lab and I call this 'community-washing'. The language is inspired by the term 'greenwashing' - wherein companies claim environmental brownie points without changing anything significant in their operations. Think of oil and gas companies releasing ads featuring windmills and solar panels despite massively investing in fossil fuels, for example.

The danger with community-washing is two-fold.

- First, that we are promised community (a rich, complex experience) but what we get is a second-rate, emoji-enabled soulless product or service that never gets anywhere deep.

- And second - more dangerously - that the poverty of community experience that we experience through these products and services diminishes what we think is possible for community itself.

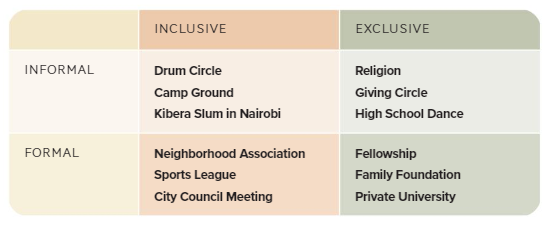

There are also stories and examples that we build together across differences and shared purpose in formal and informal ways. What do these types of actions and initiatives look like and reveal? In examining these constellations of stories we arrived at the beginnings of a typology of community that fits into a 2x2 matrix represented through formal/informal community and inclusive/exclusive community.

For example, your average, run-of-the-mill campground is representative of an informal, inclusive community. Anyone is welcome and boundaries of such a community are ever-changing as the campground becomes more or less inhabited.

A key point of revelation within our research is that so many of us are motivated by similar desires and fears in regards to how we wish to live our lives – and the act of finding our allies and conspirators in this work is of primary significance in activating change. This is why we are so excited to hold an inaugural Community Gathering in early February 2021 with 50 educators, organizers and activists, from a breadth and depth of overlapping and differing communities, who can be together in a peer-led space for true and necessary praxis of learning, connection and action.

Call to Action

How might we challenge and re-imagine our idea of community?

Our goal is to foster leadership and connectivity, to work across lines of difference, and to build social-civic muscles to engage in deep and difficult conversations in our neighborhoods, organizations, and institutions. Our essential question is: How might we challenge and re-imagine our idea of community? We’d love to hear from you. Drop us a line at [email protected], or join us for a Community Conversation on April 2, 2021, for a conversation about this research and lessons learned from our inaugural Community Gathering.

Read the full report, American Community Today.